Honestly it seems like just another phrase that’s supposed to separate “those who know” from “those who don’t.” What’s the point in saying “the Canonical Five” when we’re talking about the Ripper’s victims? Can’t we just say “Jack the Ripper’s victims” and be done with it?

Well … no. We don’t know who the Ripper really was, so we also don’t know how many people he actually killed. Depending on which book you pick up, he’s credited with anywhere from two to nine – and, at times, possibly more. The real truth is, there isn’t much we actually know about the case.

So let’s change the question slightly: who do we mean when we say “the Canonical Five”?

Mary Ann “Polly” Nichols, murdered on Friday, August 31, 1888.

Annie Chapman, murdered on Saturday September 8, 1888.

Elizabeth Stride and Catherine “Kate” Eddowes, both murdered on Sunday September 30, 1888.

Mary Jane Kelly, murdered on Friday November 9, 1888.

Were there women murdered in Whitechapel before Polly? Yes. One of them – Martha Tabram, murdered on August 7, 1888 – is frequently put forward as another of the Ripper’s victims. Another woman reported to have been murdered earlier in 1888 was later discovered to have been a newspaper invention. And there were murders after Mary Jane Kelly, some of them brutal enough to be grouped in with the Ripper murders, but for multiple reasons the case has largely been distilled to these five.

Part of it is the timing. The five women were murdered in such a short time span – a matter of weeks. The murder locations were also close together. After Mary Jane Kelly’s murder, the story was quickly taken out of the headlines – and, since she was the most gruesomely mutilated, it made sense to conclude that the Ripper had escalated and then finished. The fear and terror that had overtaken not just the East End but all of London was quickly brought to a close.

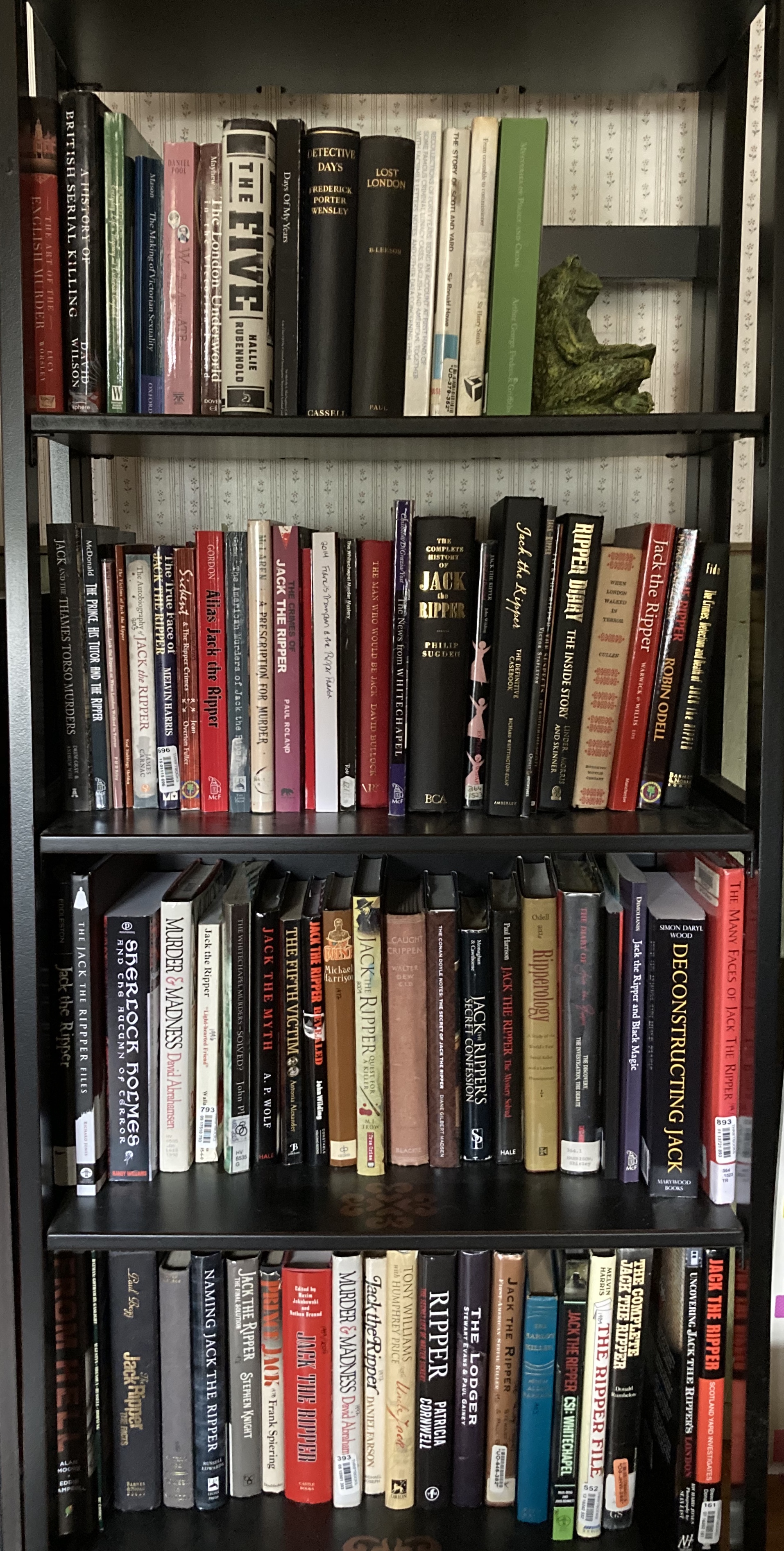

So they’re the Canonical Five not because we know for sure that they’re the only ones murdered by the Ripper, or even that he murdered all of them, but because it was concluded early on that these five deaths were related. Here’s just one of my bookshelves with Ripper books – I’ve got too many to all fit on here – and you can bet that each of them mentions Polly, Annie, Liz, Kate, and Mary Jane. Even the earliest English language Ripper book, published in 1929, agrees that all five names need to be mentioned.

So they’re the Canonical Five not because we know for sure that they’re the only ones murdered by the Ripper, or even that he murdered all of them, but because it was concluded early on that these five deaths were related. Here’s just one of my bookshelves with Ripper books – I’ve got too many to all fit on here – and you can bet that each of them mentions Polly, Annie, Liz, Kate, and Mary Jane. Even the earliest English language Ripper book, published in 1929, agrees that all five names need to be mentioned.

The biggest thing to remember about the Ripper case is that there is so much we simply don’t know. Because he was never caught, we have no confession, and therefore no idea how many people he actually killed. The term “Canonical Five” is handy because it indicates that yes, these five women have historically been grouped together, but we also acknowledge that maybe five isn’t actually the right number.

In my free time, when I’m not writing or reading about the history of true crime, I like to knit. There aren’t many serial killer-based knitting patterns (for some reason …) but I’ve got an awesome pair of mitts that look like the carpet in some famous horror movie. (I used to have a hat, too, but I’ve lost it somewhere …)

In my free time, when I’m not writing or reading about the history of true crime, I like to knit. There aren’t many serial killer-based knitting patterns (for some reason …) but I’ve got an awesome pair of mitts that look like the carpet in some famous horror movie. (I used to have a hat, too, but I’ve lost it somewhere …)