I didn’t start reading Stephen King until the summer after college. I’ve always been a voracious reader, and I can only remember one time when my parents intervened. I wanted to read Pet Sematary (it had a kitty on the cover!) but I was in second grade, so they suggested that maybe I put that one off for a while. There’s no real reason I put it off for so long, but it generally surprises people that I got such a late start.

In ‘Salem’s Lot, Catholic priest Father Callahan visits another character in the hospital and spends some time musing about how his parishioners usually react to sudden medical news like cancer, a heart attack, or stroke. Father Callahan’s experience tells him that these hospital visits are usually with someone who feels betrayed by their own body, but they can’t get away from the betrayer like they could if it was a backstabbing friend. It’s a dark assessment from a priest who’s losing his faith but who, at that point, has only really observed such things from the outside.

King was 28 when it ‘Salem’s Lot was published, and although he had personal experience with Callahan’s alcoholic, he was still decades way from the car accident that turned him into the patient. Characters like Edgar Freemantle in Duma Key (one of my favorites, and sadly not as well known) clearly come from his own lived experience, but Callahan’s dour assessment comes as an outsider.

Even though I was in my early twenties when I read it, though, it stuck with me. You can bet that scene ran through my mind after my own diagnosis.

Callahan’s not my favorite character

At least, not in ‘Salem’s Lot. He shows up again in The Dark Tower series, and although he’s not exactly young in ‘Salem’s Lot, this second appearance gives him more depth and complexity. The original Callahan is a bit whiny, wishing he had a true battle to fight for his faith. It’s one of those “Be careful what you ask for” situations, and Callahan’s one of King’s tragic characters in his initial arc. When he goes to visit the sick character in the hospital, he hasn’t really been tested himself. He means well, but he doesn’t know what he’s talking about. Callahan’s looking from the outside in.

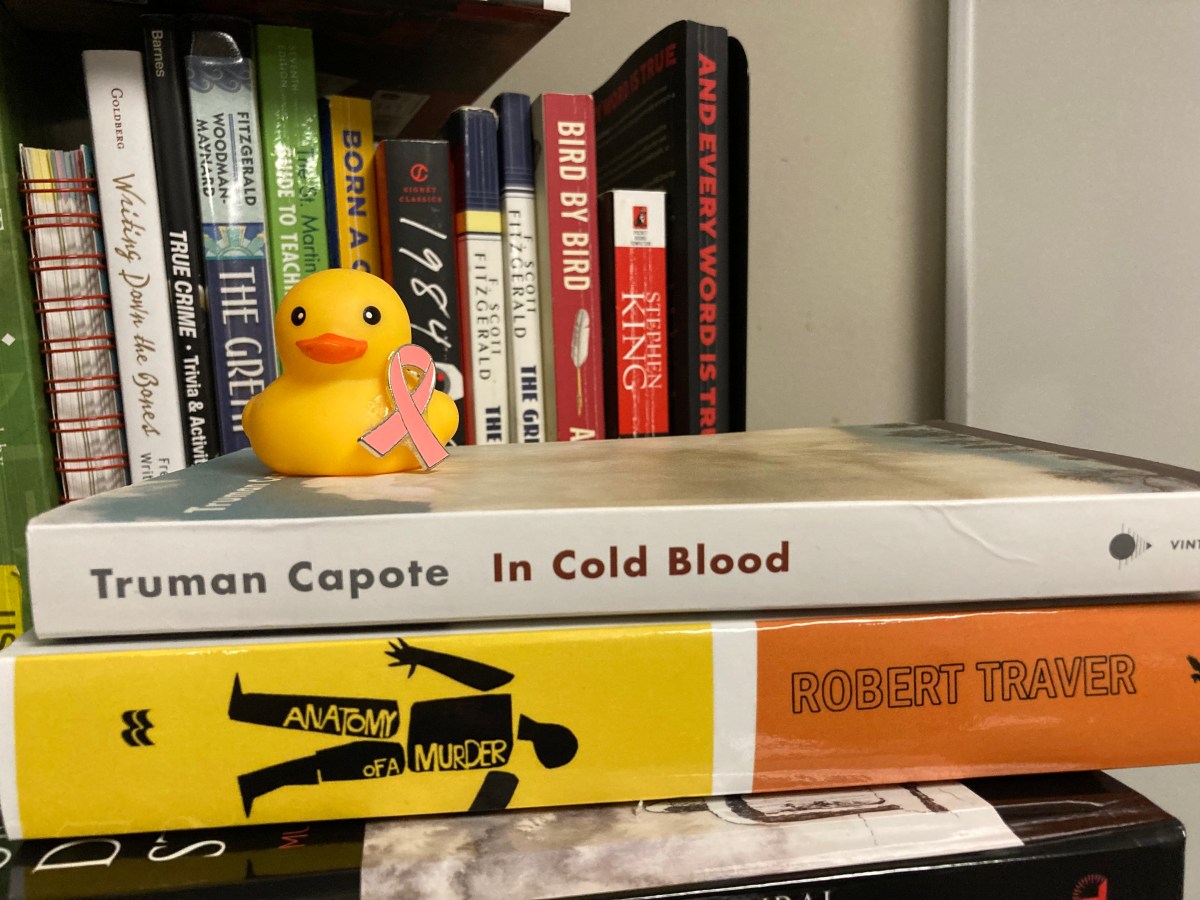

Even though I didn’t start reading King until I was older than most fans, his works are still a major component of my life. I’m the co-chair for the Stephen King area of the National Popular Culture Association conference, and I’ve written multiple chapters and two books about his works. I’ve got all his books in paper, digital, and audio formats. I’m most definitely a Constant Reader (but do not claim to be his number-one fan). Granted, King’s brand of horror isn’t exactly what you want to relate to in your daily life, anyway, but my mind automatically goes to make connections, not just from one of his books to the next, but between what he writes and what I experience.

To be fair, it’s not just King. When I was very young I read Eighty-Eight Steps to September and cried my eyes out when the main character’s little brother died from leukemia. Jan Marino just kind of paved the way for a Lurlene McDaniel phase later on. If you’ve never read one of her young adult novels, they’re full of teens going through incredibly traumatic medical diagnoses. Lots of her characters die. If the main character isn’t diagnosed with something, then their love interest is.

As we’re growing up, that’s our usual experience with intense medical issues: whatever we see or read in the media. And, let’s face it, a lot of those stories end with death. I remember my mom explaining to me that Eighty-Eight Steps to September was set far in the past (okay I think it was the fifties, but I’m trying to remember something I read in like 1991, so maybe that just felt like the far past to me at the time) and little kids don’t die from cancer like that anymore. That’s not quite true, but she had to say something to a six-year-old crying over a fictional character.

But that’s what fiction has taught me: that kind of diagnosis is an utter betrayal, once you can’t get away from, and one that’s going to end tragically.

Life imitates art?

At this point I think the most unrealistic thing about Father Callahan’s assessment is that it means his parishioners had to speed-run the stages of grief. I still have times when the thought “I had cancer” just doesn’t make sense. One of my friends said he mother-in-law sometimes gets hit with it, and her diagnosis was five years ago: “Huh. That happened. I lived through all that.” If I’m going to feel betrayed by my body, then I need to actually internalize what happened to my body.

And I also get that it’s weird to think that I should feel something just because some author somewhere put it in one of his character’s heads. It doesn’t even have to be what King himself thought back then, because he usually writes about entire towns and has plenty of opportunities to explore different points of view. It’s just a scene that was so vivid, something Callahan dwelt on in his own mind for quite a while, that it stuck. When you have cancer or a heart attack or a stroke, you feel like your body’s betrayed you.

I’ve actually spent a lot of time thinking about it. To my mind, the cancer isn’t a betrayal by my body, because it’s not me. It’s like a little mutant invasion. (Now y’all might also need to reassess how well you think I’m coping. The journey’s a long one.)

The other side of things—the Lurlene McDaniel side of things—means trying to work the whole “It’s statistically unlikely I’m going to die from this” thing into any initial announcement. Cancer is a big scary word, and the people who care about you want to know how bad it is. If caught early, invasive ductal carcinoma has a 5-year survival rate of 99%. I’m too old to be a Lurlene McDaniel heroine, anyway, but the odds were in my favor.

That doesn’t mean nobody asked if I was going to die. You can kind of guess how the age of the person in question factors into things, because hey, the younger you are, the more likely it is that your only association is cancer equals death. But even calling it “breast cancer” means there are so many possibilities for how things are going to unfold. People who’ve watched loved ones on their own journeys had more questions, and maybe more worries, than others. They had a better, more personal understanding.

Wait, so should authors stop writing outside their own lived experience?

Okay, that’s a whole can of worms and there are no easy answers. When it comes to the experience of cancer patients, though … yeah, it’s still complicated. Stephen King, writing before I was born, had no idea how much that scene would stick in my head when I read it later, or how it would come back after my diagnosis. Lurlene McDaniel started writing to deal with her son’s medical diagnosis, and honestly I think she can be credited for teaching a lot of us about the different conditions she gave her characters. That’s not something the average teen can just sit down with their parents for an in-depth discussion.

I also think that these approaches come from a place of empathy. Authors can’t always write characters who are only like themselves, so they have to try to imagine all kinds of different people whose experiences and thought processes aren’t the same. Cancer and other major medical events happen in the real world, so leaving them out completely, especially over as many books as King has written, would be unrealistic. And honestly, if I’m struggling to understand my own experience, then I can’t really fault someone who’s never gone through it for writing something different than what I’m feeling. Heck, other survivors have entirely different experiences, and that doesn’t make them wrong.

In the spirit of books and scenes that maybe stuck with you longer than they should, recommend your favorite book to a friend or post about it online. Share the love for your favorite author. Read new stories, expand your horizons, and memento vivere.