The more you write, the better you get at it – the same as practicing any other craft. And on top of writing, you can read (or watch YouTube videos, attend seminars, or buy master classes) about writing. You can get degrees and get published and all the rest, but … does there ever come a time when all the rules and practice mean that your first draft is going to come out perfectly? Well …

As my friend Bob Kubiak tweeted yesterday, “in the moment you’re working, most writing advice is forgettable.”

You can memorize all the rules – no adverbs, said is dead, pick your favorite – but, when it’s time to actually get the words on the page, that’s not what’s in your head. You’re just trying to get it down, to beat the blank space, and especially if the “rules” make you freeze … they go out the window.

Writing is hard. Even if you’re good at it and you enjoy it, it’s hard. How do you get this idea that’s here, in your own head, and turn it into words that will put the same idea into someone else’s head? How do you catch someone’s attention at the beginning and hold it all the way through? How do you make sure that there’s a clear purpose for every point, and it’s all connected with beautiful transitions?

You don’t. Not on the first round. It’s called a rough draft for a reason, and although maybe you get a little smoother the longer you write, they’re still … rough. It’s not supposed to be perfect, and if you really want to be a writer, you’ll have to learn that editing is just as important.

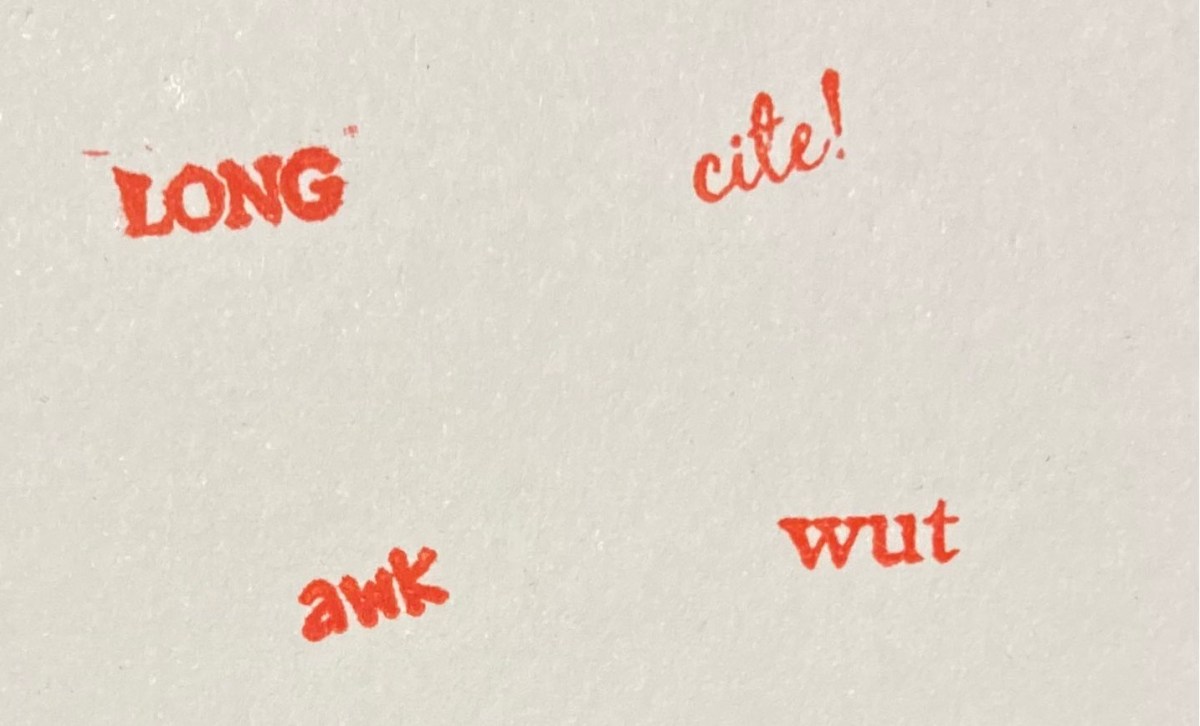

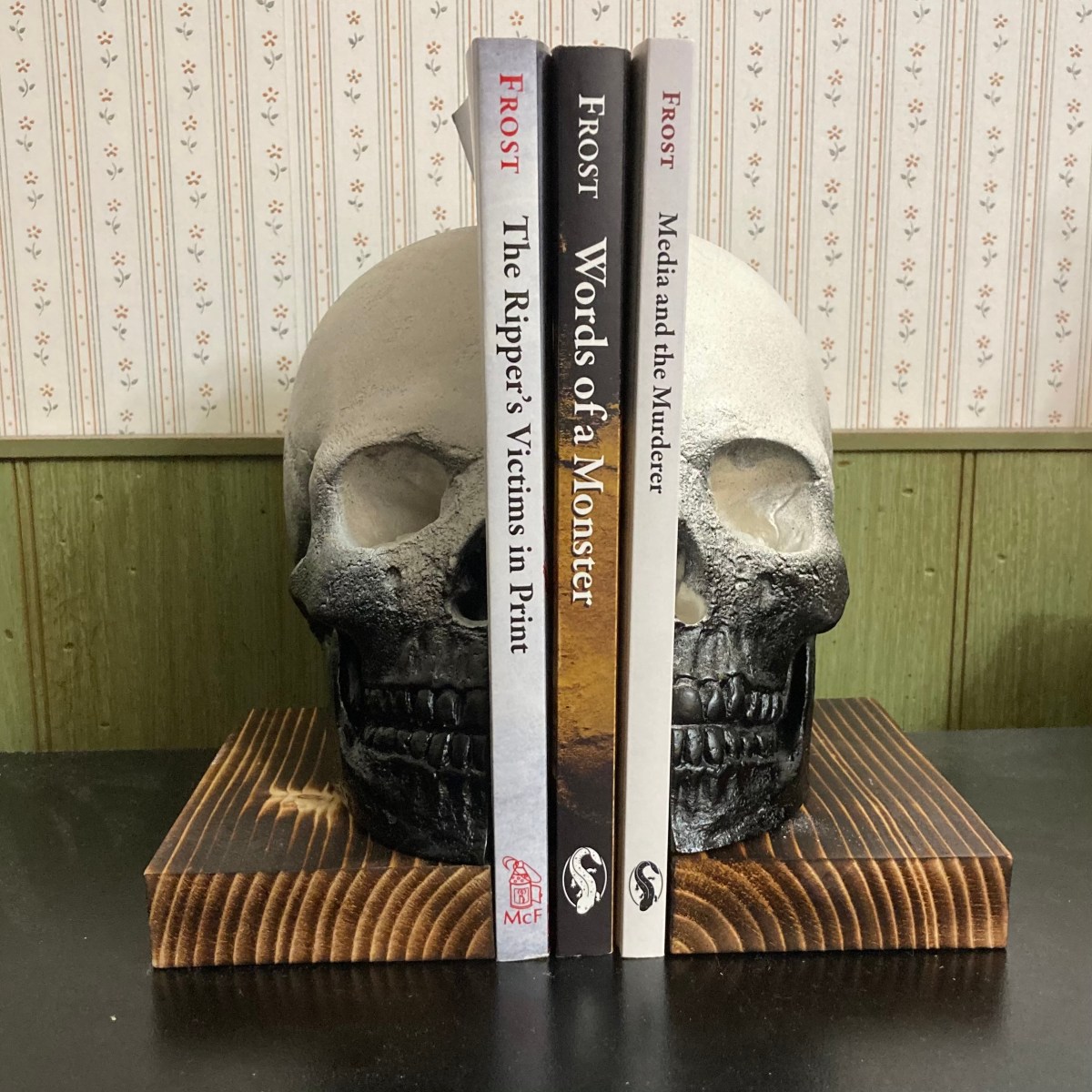

The more I write, the more I recognize my usual first-draft pitfalls. The header photo shows the self-inking stamps I bought for this round: LONG, cite!, awk, and wut. These are four things I find myself writing frequently on my first draft and correcting before anyone else even sees my writing. I’m a big fan of long, meandering sentences; saying things I don’t back up; awkward wording; and just … who even knows? In the moment, I wrote something just to keep the cursor moving so I could get the ideas down on the page, and it doesn’t make sense when I read it later.

But it’s okay. And it’s more than just okay – this is all part of the process. Writing isn’t “one and done.” You don’t bang it out and turn it in. You don’t even bang it out, skim it for spelling errors, and turn it in.

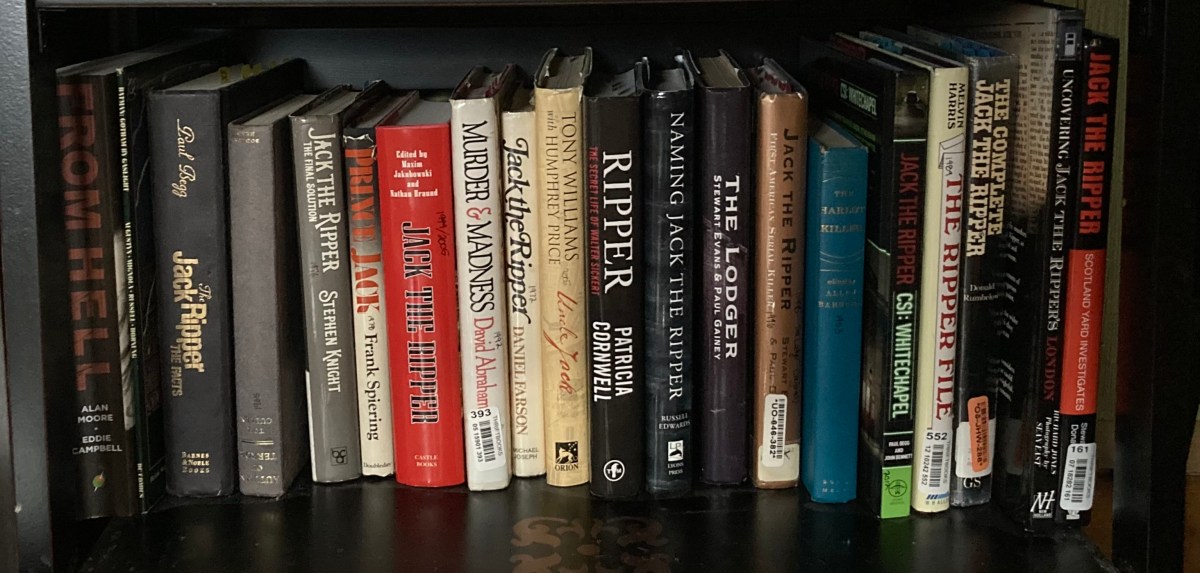

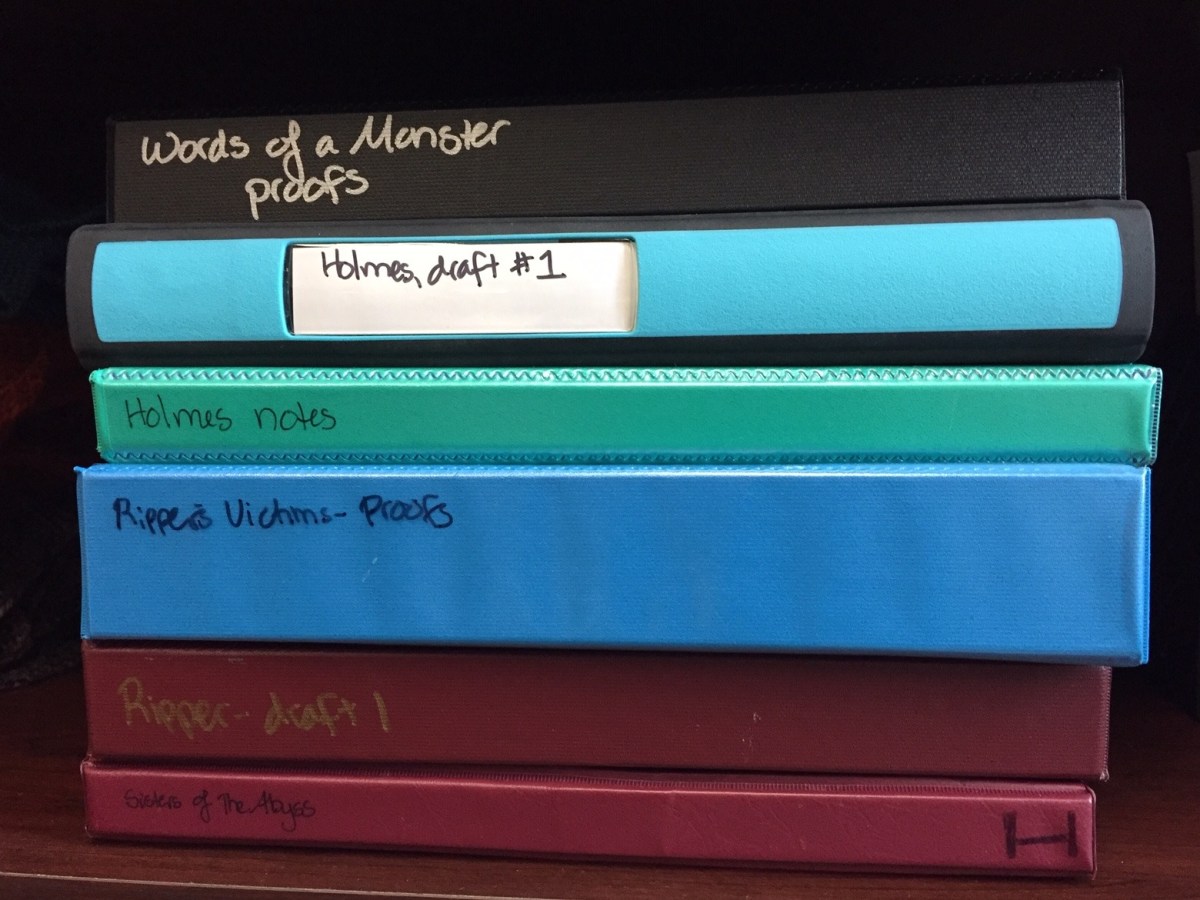

When I set a deadline for a book being due, I have to build all of this in to my personal timeline. I need the chapters drafted by this date, so I can do an initial pass and write the conclusion, but still have time to let it sit before a second pass at more of a distance. And it’s far more than just these four stamps – I’m looking for places where I latch onto a word and want to use it 20 times in a row, or places where transitions are rough (or missing), or places where I get off on a tangent and forget my point.

The function of the rough draft is, in fact, to be rough. There are going to be problems with it. The thing I’ve learned is that you can let it have problems – if you need to forget the rules long enough to get the first draft down, go for it. Give yourself permission to break every single writing rule you’ve ever heard.

Then, when you go back to edit, figure out which ones you really should adhere to.

Writing rules exist for reasons, and if you can understand why people hand out the edicts they do, you can also choose whether or not your work needs to follow it. Your edited work, of course – your rough draft doesn’t have to be readable to anyone but you, and every book or article you’ve ever read has been gone over time and again, usually by multiple people, to make sure the writing gets ideas across as clearly as possible.

Do rough drafts get a little less rough? Sometimes. But some days they’re just as messy as they’ve always been … and that’s okay. All writing has to be edited, but you can’t edit a blank page.