It’s one of the last steps needed before a nonfiction book can be published, but it’s also tedious … annoying … and incredibly necessary: the index.

I recently finished creating the one for my most recent book, Media and the Murderer: Jack the Ripper, Steven Avery and an Enduring Formula for Notoriety, and I got a lot of surprised responses: wait, a person has to do that? Why?

There are a number of reasons why it takes a human to sort through a book to make the index actually … useful.

For example, I reference the Duke of Clarence and Avondale; Prince Albert Victor; and Prince Eddy … and they’re all the same person. A computer could be asked to search for and categorize all proper nouns, but someone along the line has to recognize that they’re all the same person. (And add in the cross-references in the index to make sure that someone who knows him as Prince Eddy can find all the references.)

The proper nouns are probably the easier ones to find, too. When I’m scanning through a page to see what to underline for the index, the capital letters help.

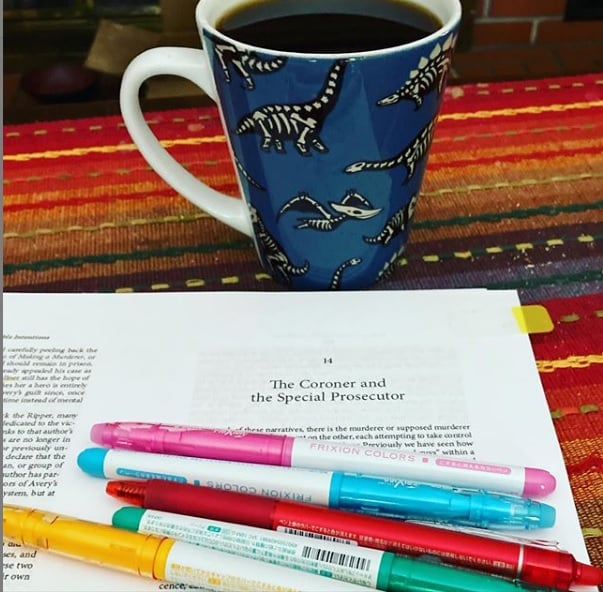

This time around I settled on four colors to help me sort through what was going on and keep the ideas in mind as far as what I was looking for. Green was general; blue referred to the murdered women; yellow was names of secondary importance; and prink referred to Jack the Ripper and Steven Avery.

There’s another rule of thumb here: if it’s mentioned in your title – as the Ripper and Avery are – then they’re on a lot of pages and they don’t get their own entry. The Ripper mentions got divided into their own categories (although there’s always the chance that this might get changed once someone at the publisher has a look and maybe a chuckle – things have been consolidated before) but what happens with Steven Avery, the main subject of Making a Murderer?

He gets his name, yes, but not a list of pages where he’s mentioned. If you know anything about MaM, you know he’s got a wrongful conviction and an exoneration – and those two categories go under his name with page numbers to follow. Instead of just being one big blob of Steven Avery mentions, he gets categorized.

The same thing can happen with some of the people I label as secondary figures. Ken Kratz, for example, has a “press conference” category, and Brendan Dassey has his “confession.” So even when it’s an easy search for someone’s name, there’s still some parsing going on. What do I think people who pick up this book might be looking for? How can I make it easier for them to find it (and therefore cite me)?

But it’s a pain. I groan at my past self for making all sorts of connections to serial killers both factual and fictional, because each mention is another entry in the index. Zac Efron, Mark Harmon, Johnny Depp … they’re all in this one. Hannibal Lecter is on multiple pages. Ted Bundy, John Wayne Gacy, Jeffrey Dahmer … they all go in the index.

Aside from the proper nouns, there are certain themes that happen to appear in my work. Some of them were major players in my dissertation: Puritan execution sermons, trial reports, and the explanation of why the adversarial trial matters. Some are specific to this book.

And the reason you do it yourself, as opposed to hiring someone else to do it, is that you know from the start what your important parts are. So therefore I knew that execution sermons had to make it in, even from the very first mention. That got underlined.

I can use the search option to go back through and make sure I’ve gotten all the pages for a certain term, as long as I remember that profiling, profiler, and profiles are all possible terms to file under “psychological profiling” … but I still need to make all of those connections so that someone who wants to use my book can know exactly where to look.

What I’ll do is write the idea down immediately. I’ve got plenty of notebooks –

What I’ll do is write the idea down immediately. I’ve got plenty of notebooks –  This is my other notebook. It’s a

This is my other notebook. It’s a

So

So

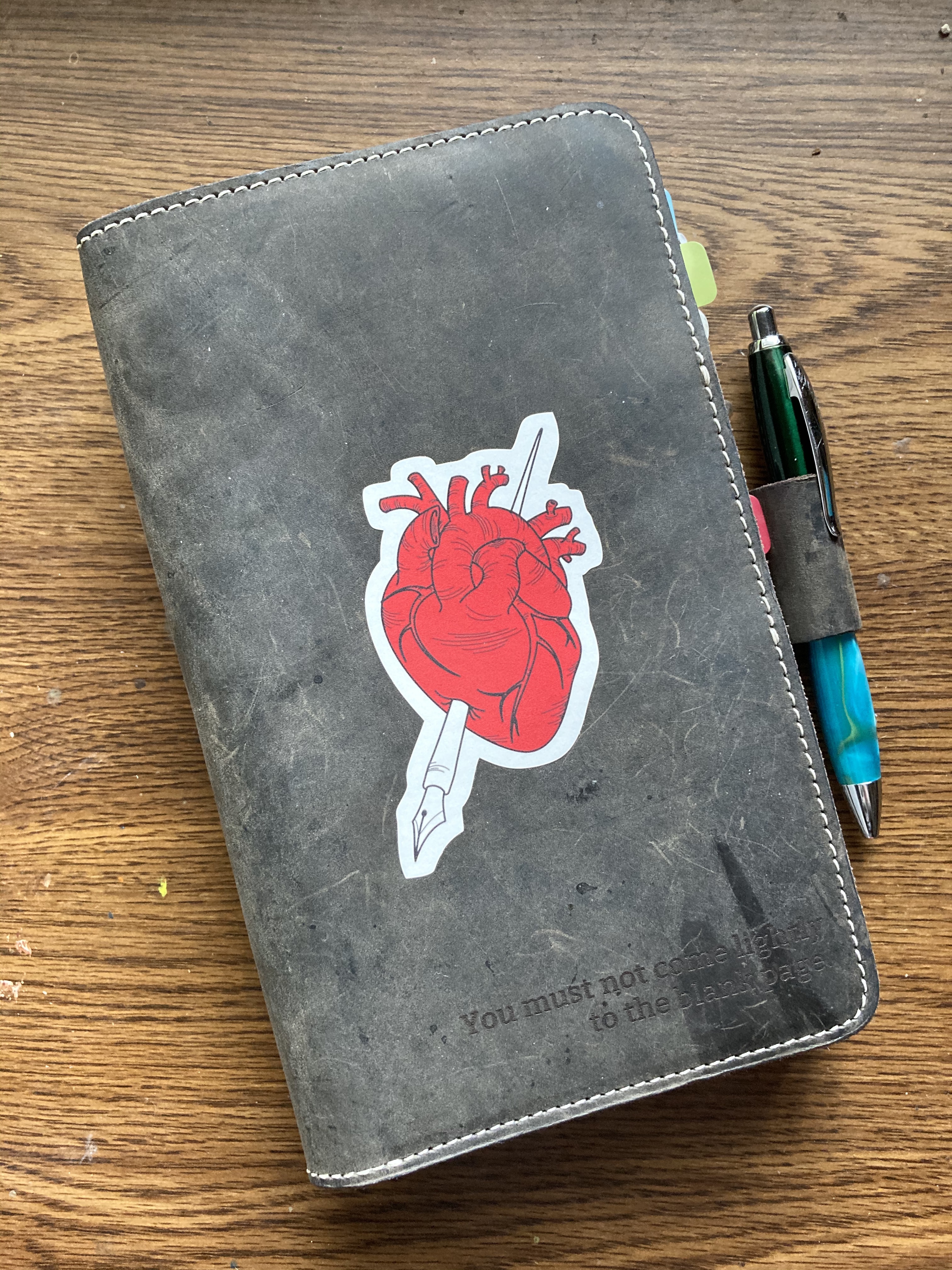

Take my most intense process so far. A call went out for people who wanted to write about heroic criminals in American popular culture. A friend of mine sent it to me and I debated, but … well, rejection on a proposal hurts far less than rejection on a full paper, so I submitted. Even before something was really written, the two editors had their eyes on it.

Take my most intense process so far. A call went out for people who wanted to write about heroic criminals in American popular culture. A friend of mine sent it to me and I debated, but … well, rejection on a proposal hurts far less than rejection on a full paper, so I submitted. Even before something was really written, the two editors had their eyes on it.

3. A progress keeper. This one is for Book Four, which is due to my editor in October, and it’s super pretty because it’s so consistent. Most of mine aren’t, but it’s important to keep track of your progress no matter what. When you’re just putting words into a computer, the only evidence that you’re actually doing anything is that you have to scroll a bit further in the file next time. I make up these little charts where each square is 500 words and I color it in at the end of the day to give myself that visual proof that I’ve at least done something.

3. A progress keeper. This one is for Book Four, which is due to my editor in October, and it’s super pretty because it’s so consistent. Most of mine aren’t, but it’s important to keep track of your progress no matter what. When you’re just putting words into a computer, the only evidence that you’re actually doing anything is that you have to scroll a bit further in the file next time. I make up these little charts where each square is 500 words and I color it in at the end of the day to give myself that visual proof that I’ve at least done something.