Remember how the you can basically accuse anyone who was alive in 1888 of having been Jack the Ripper? In 1996, author Richard Wallace decided to make the case for Charles Dodgson – pen name, Lewis Carroll. The man who wrote Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland in 1856 was meant to have murdered multiple women in 1888 … and to have confessed to all of it, if anyone happens to be clever enough to see.

The main point (slash problem) is that these confessions and clues are all in anagram form. Even then, at times Wallace needs to misspell something or otherwise get creative with his interpretations.

Most of these messages, Wallace argues, are from two of Carroll’s books: The Nursery “Alice” and Sylvie and Bruno. Both were first published in 1889, which at least works from a timing standpoint. If Carroll had been Jack the Ripper, he would have had time to commit his murders and then confess to him by the time the books went to press. So, clearly, the various lines of verse can be reworked into confessions and descriptions of the murder scenes.

Well. “Clearly.”

The problem with anagrams is that texts can be reworked to say just about anything, given a “codebreaker” with enough determination. Yes, fine, Carroll’s verse can be translated into murder confessions, but that’s only one possible interpretation … and assumes that Carroll started with his confession and worked everything backward into children’s literature. This is a level of dedication and focus at times seen in fiction, but not exactly documented in real life.

If the anagrams convince you, though, you should probably know a few other details. For example, Carroll was vacationing in East Sussex from August 31 through the end of September 1888. That covers the dates of the murders of Polly Nichols, Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride, and Kate Eddowes. On November 9, when Mary Kelly was murdered, Carroll was in Oxford.

You might point out that Wallace claims Carroll didn’t work alone – apparently this Ripper was in fact a duo and included his friend Thomas Vere Bayne – but Bayne was in Oxford with Carroll in November. Perhaps Carroll might have made multiple trips into London in order to complete these murders (a similar argument is made for suspects such as Walter Sickert and Prince Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence and Avondale, whose schedules likewise seem to leave little room for murder) but that would be an incredible stretch.

Wallace doesn’t rely solely on his anagrams. He also argues that Carroll’s life and childhood set him up as the sort of man who would indeed kill women for his own pleasure. He even argues, as many authors of the 1990s seem to, that Carroll was a victim before he ever made the murdered women his victims. In spite of these claims, though, there’s nothing in Carroll’s life that points to such acts of violence.

This theory argues that the Ripper was the sort of person who would publicize his crimes for all the world to read while laughing behind his hand because people didn’t realize the actual content of the text. True, there were all those Ripper letters that made it seem like the killer wanted to write about his crimes, and yes, Carroll was an author who wrote about many strange things, but … that seems to be the limit.

If you’re a fan of anagrams, you can turn any piece of writing into a confession of murder. Lewis Carroll is an interesting historical figure who has been examined for many reasons in both his public and personal life, but he wasn’t Jack the Ripper … even if he could be anagrammed into saying so.

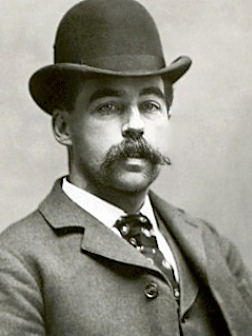

Holmgren and Norris not only point out that neither Lechmere – seen here in a photograph from 1912 – nor Paul mentioned seeing any other person in Buck’s Row, even though the murderer must have still been nearby, but map out Lechmere’s life against the murders of the Canonical Five and a previous victim, Martha Tabram. Each of these sites corresponds with Lechmere’s walk from home to work in the autumn of 1888, or to previous homes his family occupied, or earlier jobs he had.

Holmgren and Norris not only point out that neither Lechmere – seen here in a photograph from 1912 – nor Paul mentioned seeing any other person in Buck’s Row, even though the murderer must have still been nearby, but map out Lechmere’s life against the murders of the Canonical Five and a previous victim, Martha Tabram. Each of these sites corresponds with Lechmere’s walk from home to work in the autumn of 1888, or to previous homes his family occupied, or earlier jobs he had.

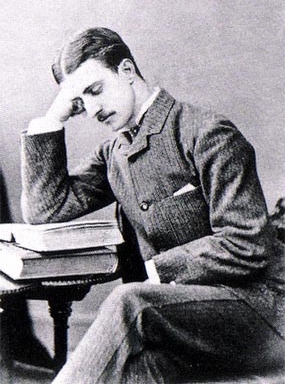

Druitt was a young lawyer who committed suicide in late 1888 after the murder of Mary Jane Kelly. He had been working at a boarding school in order to supplement his income, and was dismissed from that post in late November. There is no evidence supporting a reason for this dismissal, but Druitt killed himself not long after. His body was found floating in the Thames on December 31, 1888, and had been in the water for some time.

Druitt was a young lawyer who committed suicide in late 1888 after the murder of Mary Jane Kelly. He had been working at a boarding school in order to supplement his income, and was dismissed from that post in late November. There is no evidence supporting a reason for this dismissal, but Druitt killed himself not long after. His body was found floating in the Thames on December 31, 1888, and had been in the water for some time.

Wilding published Jack the Ripper: Revealed in 1993 and an updated version (Jack the Ripper: Revealed and Revisited) in 2006. He starts with Mary Jane Kelly, the final victim of the Canonical Five, putting her in a difficult position. Wilding’s Mary is pregnant, and the father is the Crown Prince himself. For some reason, once she discovers her pregnancy, Mary goes to lawyer Montague John Druitt to inform him of her situation.

Wilding published Jack the Ripper: Revealed in 1993 and an updated version (Jack the Ripper: Revealed and Revisited) in 2006. He starts with Mary Jane Kelly, the final victim of the Canonical Five, putting her in a difficult position. Wilding’s Mary is pregnant, and the father is the Crown Prince himself. For some reason, once she discovers her pregnancy, Mary goes to lawyer Montague John Druitt to inform him of her situation.

When they try to follow her one night, keeping track of Mary by her unique bonnet, Mary Kelly passed that bonnet to Mary Nichols in order to throw off her tail. She did not recognize Druitt and Stephen, and they did not realize that they killed the wrong woman. Thus Mary Nichols’ death was a case of mistaken identity. Mary Kelly worried that it was her bonnet that got her friend killed and told another friend, Annie Chapman. She also made the mistake of expressing the same concerns to Druitt and telling him Annie’s name, turning Annie into the second Canonical victim.

When they try to follow her one night, keeping track of Mary by her unique bonnet, Mary Kelly passed that bonnet to Mary Nichols in order to throw off her tail. She did not recognize Druitt and Stephen, and they did not realize that they killed the wrong woman. Thus Mary Nichols’ death was a case of mistaken identity. Mary Kelly worried that it was her bonnet that got her friend killed and told another friend, Annie Chapman. She also made the mistake of expressing the same concerns to Druitt and telling him Annie’s name, turning Annie into the second Canonical victim.

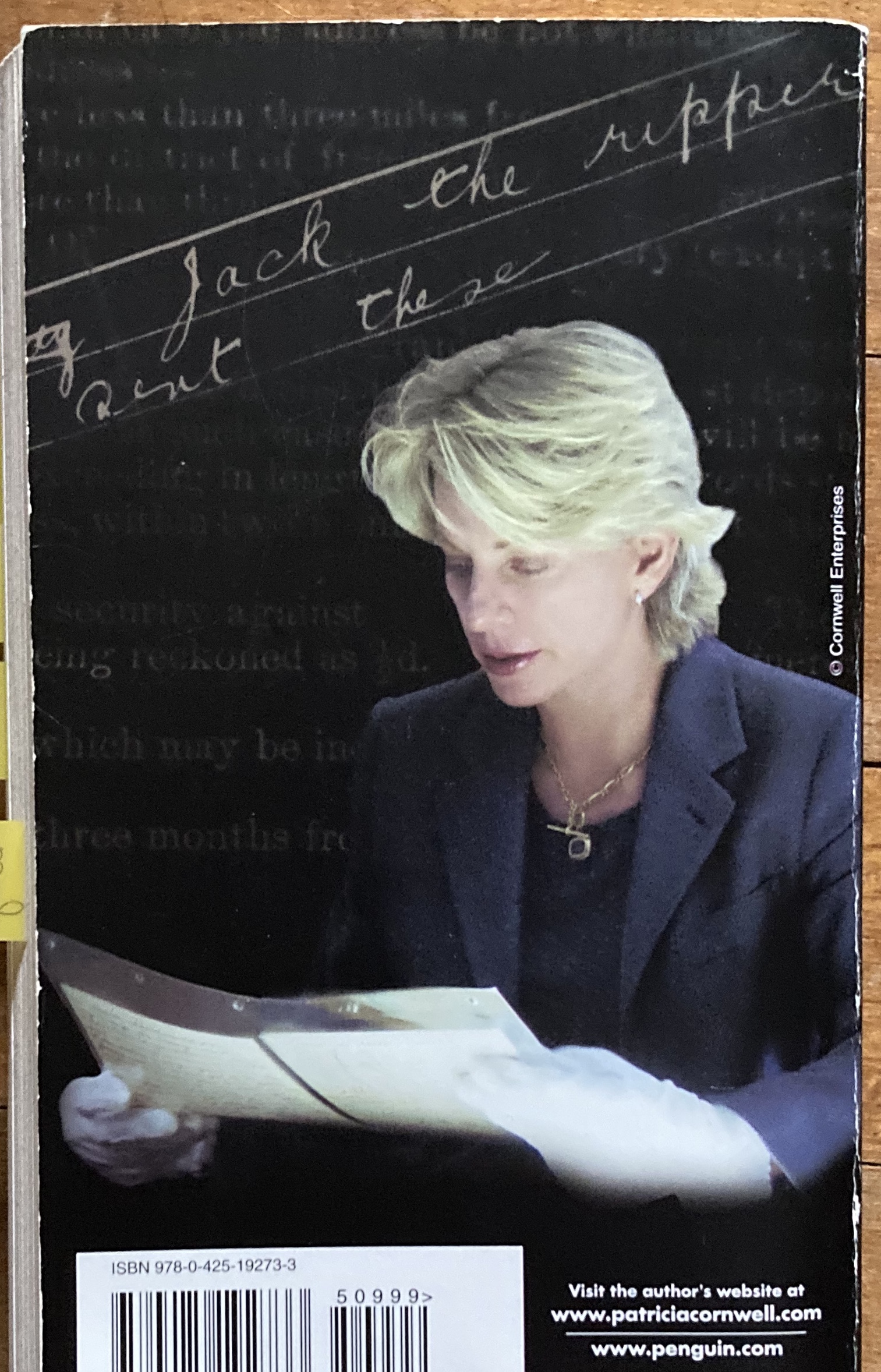

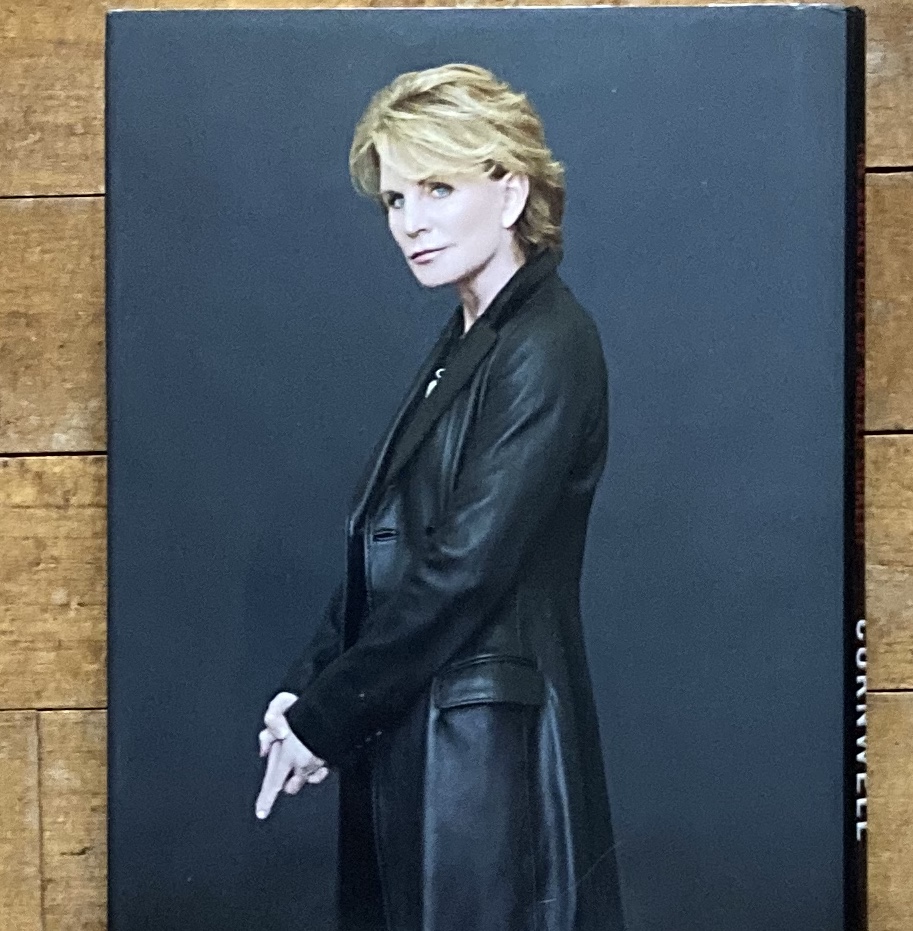

If you’ve only read one book about Jack the Ripper, chances are it’s Patricia Cornwell’s 2002 Portrait of a Killer: Jack the Ripper – Case Closed. Here she is on the back, examining a document carefully while wearing clean white gloves to apparently indicate she’s in an archive. Known for her fiction, especially her series about medical examiner Kay Scarpetta, Cornwell decided to use her personal wealth to investigate the Ripper crimes. Her research, which was updated first in a Kindle single and in a 2017 follow-up book, directed her toward accusing artist Walter Sickert as having been Jack the Ripper.

If you’ve only read one book about Jack the Ripper, chances are it’s Patricia Cornwell’s 2002 Portrait of a Killer: Jack the Ripper – Case Closed. Here she is on the back, examining a document carefully while wearing clean white gloves to apparently indicate she’s in an archive. Known for her fiction, especially her series about medical examiner Kay Scarpetta, Cornwell decided to use her personal wealth to investigate the Ripper crimes. Her research, which was updated first in a Kindle single and in a 2017 follow-up book, directed her toward accusing artist Walter Sickert as having been Jack the Ripper. There are a couple issues here, in spite of how cool she might look on the back cover of the second book in her Matrix-style coat. First, her methods assume that the Ripper himself licked the stamps and the envelopes. This means both that the letter wasn’t handed over to an employee who sold the stamp and did the honors, and that the Ripper actually wrote the letters. And second, because of the age of the letters, only mitochondrial DNA could be tested. At best, mDNA showed that Sickert could not be excluded from the tens (or possibly hundreds) of thousands of possible people who could have licked the envelope. Cornwell’s experts told her she had narrowed the Ripper down to about 1% of the Victorian British population, and in her book she translates this as indicating that yes, it was Sickert.

There are a couple issues here, in spite of how cool she might look on the back cover of the second book in her Matrix-style coat. First, her methods assume that the Ripper himself licked the stamps and the envelopes. This means both that the letter wasn’t handed over to an employee who sold the stamp and did the honors, and that the Ripper actually wrote the letters. And second, because of the age of the letters, only mitochondrial DNA could be tested. At best, mDNA showed that Sickert could not be excluded from the tens (or possibly hundreds) of thousands of possible people who could have licked the envelope. Cornwell’s experts told her she had narrowed the Ripper down to about 1% of the Victorian British population, and in her book she translates this as indicating that yes, it was Sickert. In 2007, Russel Edwards bought the shawl at auction, believing the story of its provenance when other Ripper scholars present scoffed at the idea. Like Cornwell, he had DNA tests run, this time checking for matches to two people. (Again, note the CSI-style photographs.) Edwards concluded that the blood found on the shawl could indeed have come from Catherine Eddowes, and that the semen did not exclude his personal choice for Ripper, Polish barber Aaron Kosminski.

In 2007, Russel Edwards bought the shawl at auction, believing the story of its provenance when other Ripper scholars present scoffed at the idea. Like Cornwell, he had DNA tests run, this time checking for matches to two people. (Again, note the CSI-style photographs.) Edwards concluded that the blood found on the shawl could indeed have come from Catherine Eddowes, and that the semen did not exclude his personal choice for Ripper, Polish barber Aaron Kosminski.

This is a replica of a postcard that was sent to the Central News Agency on October 1, 1888. It’s come to be known as the “Saucy Jacky Postcard,” and there are a couple interesting things about it. First, it wasn’t sent until very late that fall – after (at least) four murders had been committed and people were already talking and reading about the crimes. The second is what it says:

This is a replica of a postcard that was sent to the Central News Agency on October 1, 1888. It’s come to be known as the “Saucy Jacky Postcard,” and there are a couple interesting things about it. First, it wasn’t sent until very late that fall – after (at least) four murders had been committed and people were already talking and reading about the crimes. The second is what it says:

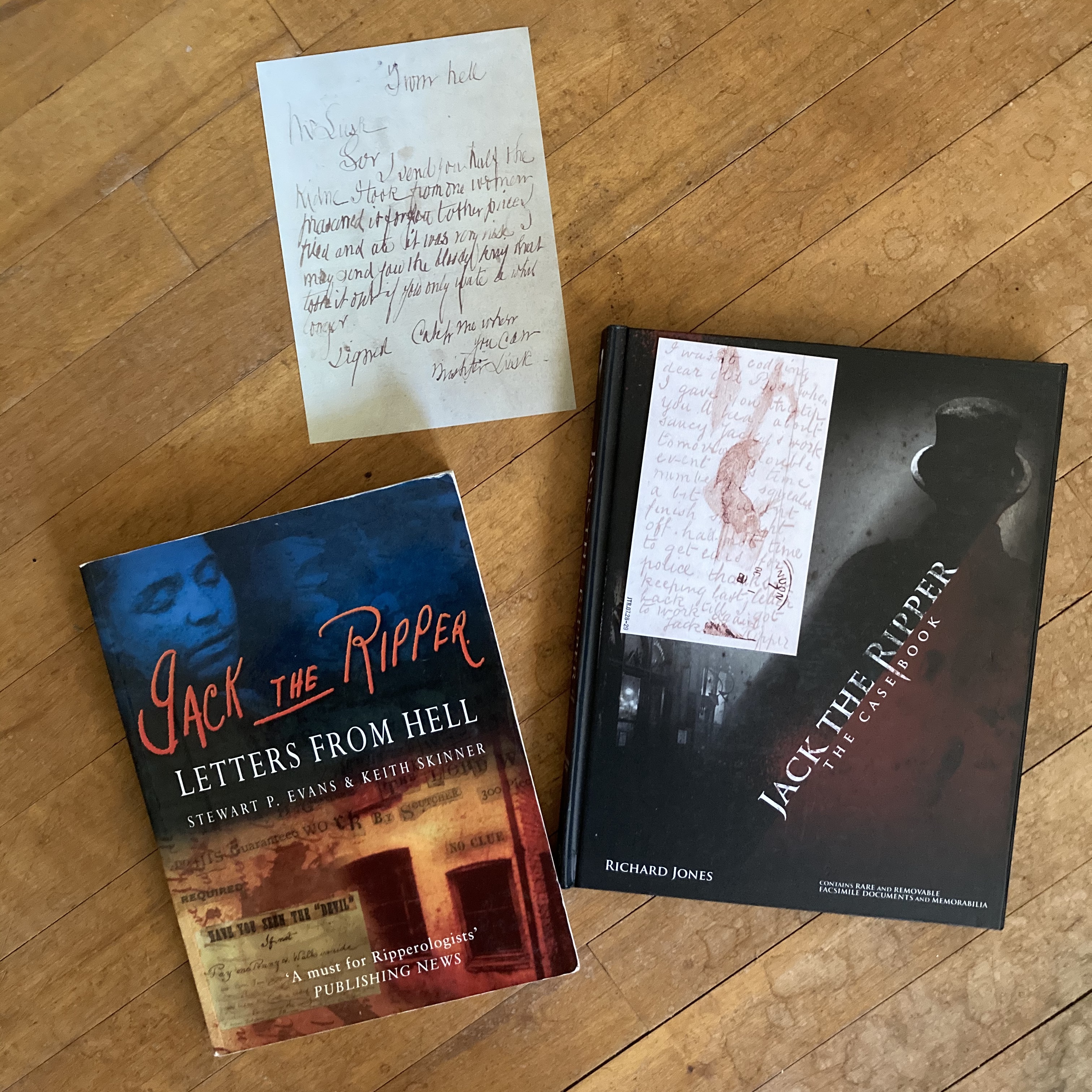

More than 300 letters were sent – to the police, to newspapers, and to the Central News Agency – claiming to be from the killer. There are entire books devoted to these letters, like Jack the Ripper: Letters from Hell by Stewart P. Evans and Keith Skinner, and stories of young women being arrested for being caught sending them. The letters are interesting, having both kept the murders in the news and given the killer his name … but are any of them real?

More than 300 letters were sent – to the police, to newspapers, and to the Central News Agency – claiming to be from the killer. There are entire books devoted to these letters, like Jack the Ripper: Letters from Hell by Stewart P. Evans and Keith Skinner, and stories of young women being arrested for being caught sending them. The letters are interesting, having both kept the murders in the news and given the killer his name … but are any of them real?