I can hear you: “Rebecca, you’ve spent three weeks talking about H. H. Holmes, but you haven’t mentioned his murder castle.” It’s the coolest part, right? Man gets his medical degree, moves to Chicago, and starts to build this mysterious three-story building with a “glass-bending oven” in the basement that was totally used to cremate his victims and all sorts of mysterious rooms where he can lock people in vaults or let gas inside. Plus some sort of chute to get people from the second to the first without heavy lifting. During the World’s Fair he killed hundreds of people, so why hasn’t this been mentioned yet?

If you knew about Holmes before – and especially if you’ve been eagerly anticipating the murder castle discussion – I’m guessing you learned about him from Erik Larson. The Devil in the White City: Murder, Magic, and Madness at the Fair that Changed America. Larson interweaves Holmes’ story with that of the Columbian Exposition, paralleling the construction of the Fair with the construction of Holmes’ murder castle. The story bounces back and forth until the Fair is over and Holmes can have the pages to himself on his final, strange, itinerant spree, but, during his time in Chicago, Larson depicts Holmes very much as the happy serial murderer, using his mysterious Castle as a human version of a roach motel.

If you knew about Holmes before – and especially if you’ve been eagerly anticipating the murder castle discussion – I’m guessing you learned about him from Erik Larson. The Devil in the White City: Murder, Magic, and Madness at the Fair that Changed America. Larson interweaves Holmes’ story with that of the Columbian Exposition, paralleling the construction of the Fair with the construction of Holmes’ murder castle. The story bounces back and forth until the Fair is over and Holmes can have the pages to himself on his final, strange, itinerant spree, but, during his time in Chicago, Larson depicts Holmes very much as the happy serial murderer, using his mysterious Castle as a human version of a roach motel.

In his notes, Larson explains that he did not use the internet during his research. Instead he used a lot of newspapers … and newspapers wanted to share the lurid, the outlandish, and the scandalous so they could sell. It makes a for a good story, sure, but the papers already did a ton of extrapolating and connecting the dots before Larson got to them and constructed his own narrative. It’s a good story, but if that’s your only source on Holmes, you’re missing a lot.

The counter to Larson is one I tell people not to read if they were so starry-eyed over Larson’s Holmes that they can’t picture him any other way. Adam Selzer’s H. H. Holmes: The True History of the White City Devil pulls back the curtain and explains that, well, the murder castle really wasn’t all you thought it was. He describes clerks from the shops on the first floor napping in those “secret” rooms and passageways, and argues that it really wasn’t used as a hotel, after all. When a fire broke out in the middle of the night during the World’s Fair, there weren’t nearly enough people on the street to argue that the third floor was actually being used that way. (Selzer also gives talks and tours, and you can catch him online, although I’d recommend acquainting yourself with the case first, either through his book or some of your own research – he can jump around a lot for people who come in with only the faintest idea of who Holmes is and what myths need to be debunked.)

The counter to Larson is one I tell people not to read if they were so starry-eyed over Larson’s Holmes that they can’t picture him any other way. Adam Selzer’s H. H. Holmes: The True History of the White City Devil pulls back the curtain and explains that, well, the murder castle really wasn’t all you thought it was. He describes clerks from the shops on the first floor napping in those “secret” rooms and passageways, and argues that it really wasn’t used as a hotel, after all. When a fire broke out in the middle of the night during the World’s Fair, there weren’t nearly enough people on the street to argue that the third floor was actually being used that way. (Selzer also gives talks and tours, and you can catch him online, although I’d recommend acquainting yourself with the case first, either through his book or some of your own research – he can jump around a lot for people who come in with only the faintest idea of who Holmes is and what myths need to be debunked.)

So: what’s up with the so-called murder castle?

We know that Holmes had it built. We also know that, as a con man, he had a practice of hiring workers, refusing to pay them, and then hiring more. This wasn’t so that no single person would know the entire layout of the building, but so he simply didn’t have to pay them. We know there were shops on the first floor – and that one of his mistresses and likely victims was the wife of one of the men employed in said shops – and that much was made during the excavation of the basement. Newspapers reported in large headlines that bodies had been found … and then days later, in smaller print hidden somewhere other than the front page, that really it was maybe only a single body.

All of this suspicion and excavation happened while Holmes was in Philadelphia, making headlines because of the Pitezel case. Remember, at the beginning Holmes was wanted for a single murder: Benjamin Pitezel. But, the longer he sat in jail and the longer the police puzzled over his mysterious story, the mystery continued to grow. He was now suspected of murdering Alice, Nellie, and Howard Pitezel, too.

And so, Chicago asked itself, if the man had been living here before that … couldn’t we make something of it, too? Instead of writing postcards to the papers claiming to be the killer, Chicago reporters took what they had and let their imaginations run with it, increasing the myth of who Holmes was, what he had done, and how many he had killed.

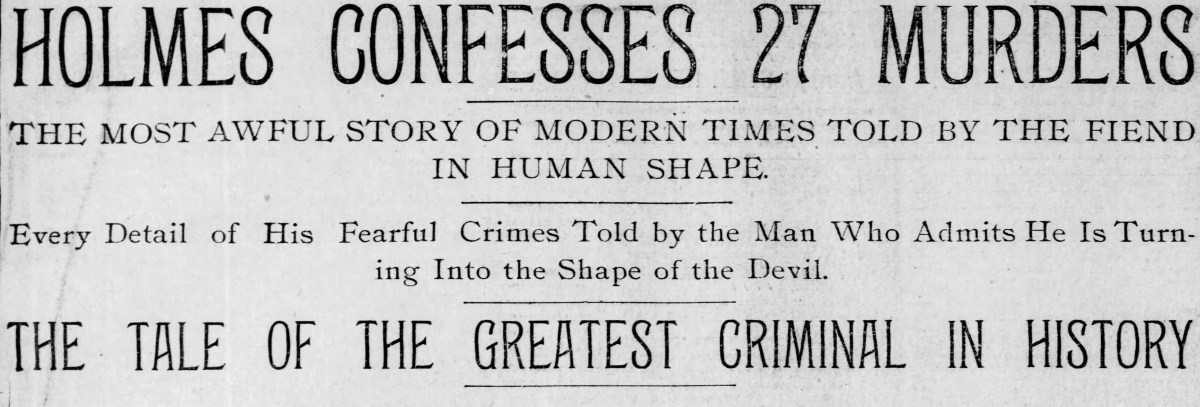

Not, it seems, that Holmes minded, considering his confession of 27 murders and the fact that many of them were made up out of whole cloth. Holmes the con man would be thrilled to know that people think he killed 250 people or more – and got away with all of them until he slipped up with Benjamin Pitezel. As someone who participated in his own myth-making while he was alive, Holmes would be happy to know he’s still being discussed so long after his death.

He’s bumped up the number, certainly. At the trial Holmes was accused of a single murder – even the deaths of Alice, Nellie, and Howard Pitezel were not mentioned, since they did not happen in Pennsylvania. Now he’s progressed to “the greatest criminal in history” with 27 murders.

He’s bumped up the number, certainly. At the trial Holmes was accused of a single murder – even the deaths of Alice, Nellie, and Howard Pitezel were not mentioned, since they did not happen in Pennsylvania. Now he’s progressed to “the greatest criminal in history” with 27 murders. First, he lied. Some of the people Holmes named actually came forward before his execution two weeks later to inform the world that Holmes had not, in fact, murdered them.

First, he lied. Some of the people Holmes named actually came forward before his execution two weeks later to inform the world that Holmes had not, in fact, murdered them.

What I’ll do is write the idea down immediately. I’ve got plenty of notebooks –

What I’ll do is write the idea down immediately. I’ve got plenty of notebooks –  This is my other notebook. It’s a

This is my other notebook. It’s a

First confession in Boston, right after being taken into custody: at this point nobody was all that concerned about the children, so Holmes said that they were with their father, Benjamin. Who was totally alive. In South America somewhere, but totally alive. He had first stolen and then mutilated a corpse to be buried in Pitezel’s place.

First confession in Boston, right after being taken into custody: at this point nobody was all that concerned about the children, so Holmes said that they were with their father, Benjamin. Who was totally alive. In South America somewhere, but totally alive. He had first stolen and then mutilated a corpse to be buried in Pitezel’s place. This is also where Holmes switched from spoken explanation to written. Holmes’ Own Story, published before his autumn trial for Benjamin Pitezel’s murder, is a multi-part book that starts with Holmes’s autobiography. It continues into the second part which is meant to be his prison diary. Then, once the diary structure falls apart, he finally gets around to his explanation of how Alice, Nellie, and Howard could be dead … but it wasn’t his fault.

This is also where Holmes switched from spoken explanation to written. Holmes’ Own Story, published before his autumn trial for Benjamin Pitezel’s murder, is a multi-part book that starts with Holmes’s autobiography. It continues into the second part which is meant to be his prison diary. Then, once the diary structure falls apart, he finally gets around to his explanation of how Alice, Nellie, and Howard could be dead … but it wasn’t his fault.

So

So

Please meet H. H. Holmes. If you did actually meet him, though, sometime between his birth in 1861 and his execution in 1896, he might not have given you that name. He was born Herman Webster Mudgett and didn’t adopt the Holmes name until he’d completed medical school at the University of Michigan and then moved away from home (and his first wife).

Please meet H. H. Holmes. If you did actually meet him, though, sometime between his birth in 1861 and his execution in 1896, he might not have given you that name. He was born Herman Webster Mudgett and didn’t adopt the Holmes name until he’d completed medical school at the University of Michigan and then moved away from home (and his first wife).

Detective Geyer made use of the newspapers in his search of the various cities so that he didn’t have to keep explaining himself to various realtors. In Toronto, he gave an interview to numerous reporters so that the story of Holmes and the three children became front-page news. After this, he only had to walk in for the realtor to tell him no, he had never rented to anyone matching Holmes’ description – or that yes, he did indeed remember a man using Holmes’ favorite cover story. Geyer was able to speed through his list of realtors and find the house where Alice and Nellie had been killed.

Detective Geyer made use of the newspapers in his search of the various cities so that he didn’t have to keep explaining himself to various realtors. In Toronto, he gave an interview to numerous reporters so that the story of Holmes and the three children became front-page news. After this, he only had to walk in for the realtor to tell him no, he had never rented to anyone matching Holmes’ description – or that yes, he did indeed remember a man using Holmes’ favorite cover story. Geyer was able to speed through his list of realtors and find the house where Alice and Nellie had been killed.

Take my most intense process so far. A call went out for people who wanted to write about heroic criminals in American popular culture. A friend of mine sent it to me and I debated, but … well, rejection on a proposal hurts far less than rejection on a full paper, so I submitted. Even before something was really written, the two editors had their eyes on it.

Take my most intense process so far. A call went out for people who wanted to write about heroic criminals in American popular culture. A friend of mine sent it to me and I debated, but … well, rejection on a proposal hurts far less than rejection on a full paper, so I submitted. Even before something was really written, the two editors had their eyes on it. Finding it is usually the problem. Past Rebecca was good about making notes, but she also tended to write them longhand. Take a look here – these are my notes from my independent study course on Jack the Ripper’s victims from way back in 2011. The box is full. That’s a lot of information. And at least it’s divided by subject, with sources up front, and at least Past Rebecca had neat handwriting, but … that’s not the easiest thing to search. It’s a nice physical representation of the research that went into that paper, which turned into my first conference presentation and then my first book. Still, it’s not very user-friendly.

Finding it is usually the problem. Past Rebecca was good about making notes, but she also tended to write them longhand. Take a look here – these are my notes from my independent study course on Jack the Ripper’s victims from way back in 2011. The box is full. That’s a lot of information. And at least it’s divided by subject, with sources up front, and at least Past Rebecca had neat handwriting, but … that’s not the easiest thing to search. It’s a nice physical representation of the research that went into that paper, which turned into my first conference presentation and then my first book. Still, it’s not very user-friendly. Oh, I still print things off. Here’s my notebook that I worked from while writing Ripper’s Victims. You can see some of my quirks – teeny font, two columns, printed sideways and then stuck in sheet protectors so I can scribble over it with markers. I find it’s easier to have the pages sitting by my laptop when I’m working on that specific section, and if you know me, you know I love my colored pens.

Oh, I still print things off. Here’s my notebook that I worked from while writing Ripper’s Victims. You can see some of my quirks – teeny font, two columns, printed sideways and then stuck in sheet protectors so I can scribble over it with markers. I find it’s easier to have the pages sitting by my laptop when I’m working on that specific section, and if you know me, you know I love my colored pens.

3. A progress keeper. This one is for Book Four, which is due to my editor in October, and it’s super pretty because it’s so consistent. Most of mine aren’t, but it’s important to keep track of your progress no matter what. When you’re just putting words into a computer, the only evidence that you’re actually doing anything is that you have to scroll a bit further in the file next time. I make up these little charts where each square is 500 words and I color it in at the end of the day to give myself that visual proof that I’ve at least done something.

3. A progress keeper. This one is for Book Four, which is due to my editor in October, and it’s super pretty because it’s so consistent. Most of mine aren’t, but it’s important to keep track of your progress no matter what. When you’re just putting words into a computer, the only evidence that you’re actually doing anything is that you have to scroll a bit further in the file next time. I make up these little charts where each square is 500 words and I color it in at the end of the day to give myself that visual proof that I’ve at least done something.