I know I’ve already shared how I, personally, outline books – or, at least, how I outlined Ripper’s Victims specifically – but since I’ve also pointed out that each new project can feel like learning to write all over again (and since that first post is pretty darn old by now) I thought I’d come back to this question with a broader scope.

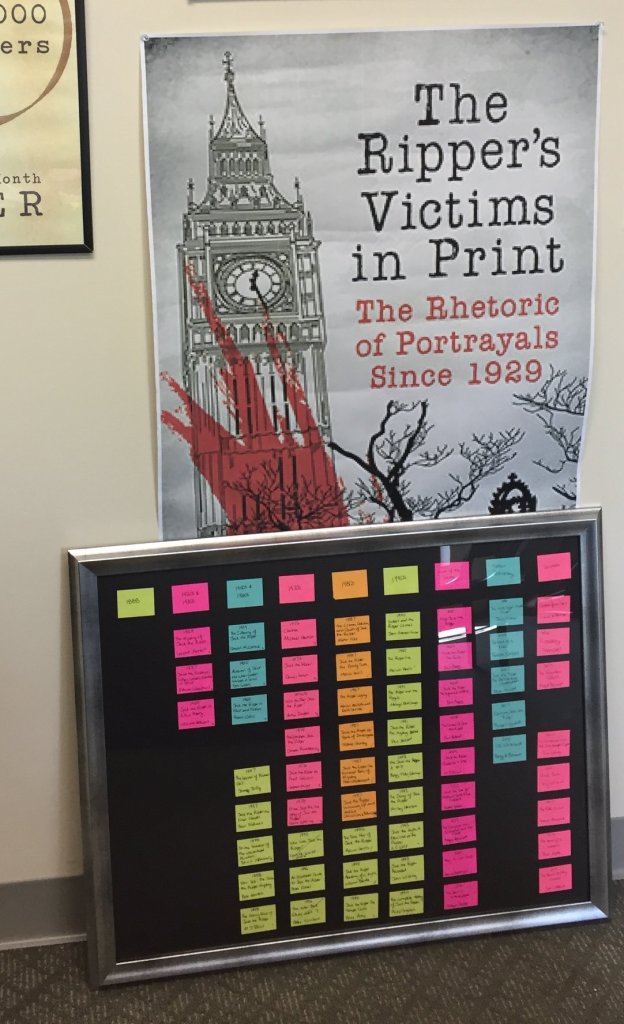

Yes, I outlined Ripper’s Victims using sticky notes before I ever started writing it. Yes, I’ve still got that poster board. And there are a lot of times I use sticky notes and poster boards to organize my ideas in the early phases, especially of nonfiction projects, but of course that’s not the only way.

I have friends who:

- jump right into a project without any notes or outline or anything. She just sits down, goes “Hmmm,” and writes the first page. And it works. She’s written entire novels this way.

- come to the first page with a pretty detailed world and the first couple scenes in mind, then see where that takes them.

- outline everything very meticulously. And I mean very. To the point where it’s less of an outline and more … nearly-completed scenes. But she doesn’t like revising, and she can manage to keep up the energy not only of these outlines, but also then writing the book.

They’ve also all written more than one project, so these methods are the ones they’ve figured out to help them keep moving forward. It’s like Stephen King‘s “Write every day” advice (I wrote my own thoughts on that here): it works for him because he knows what doesn’t work for him. My outlining friend does so much work before “officially” writing because she’s seen what happens if she doesn’t. The friend who writes by the seat of her pants hasn’t had to change her method because it works for her.

And along with the “each project is new” aspect of it, I’ve also realize that – shock, I know – there are major differences between my nonfiction and my fiction approach.

I don’t outline my fiction with sticky notes.

Sorry. I should’ve warned you. That one’s probably a big shocker.

For Not Your Mary Sue, I don’t think I have any written notes … at all … before starting it for NaNoWriMo (at 12:01am November 1, because I’ll force myself to wait for November, but no longer). Even though the idea had been in my head since February that year.

I’d been thinking about Marcy, and her family, and her background, and how she’d react to waking up on that island, but I don’t have any character sheets written down. No timelines drawn out. I “cast” Jay in my head but I had even less on his background than Marcy’s.

Since it’s from Marcy’s POV, she was the one I needed to know better. I also knew Jay’s main goal would be talking and telling her all about himself, so … I figured that I’d be able to learn along with her. (Hey, it’s a first draft. Nobody ever has to see your first draft. If it crashed and burned, nobody ever had to know.)

And the thing is, the story I thought I’d be writing ended up being only about half of what actually came out. I saw where it could go, to a specific point, and assumed I’d then write a little tag scene to sort of wrap things up, but … the story didn’t want to be wrapped up there. I knew who Marcy was by then, had spent so much time with her, and realized her story wasn’t done yet.

So I had even less of an idea of how the second half of the book would go, but I followed her anyway and let her do her things and live her life, and followed her like Joe Goldberg and wrote it all down. (Maybe someday I’ll share how I thought Marcy’s story “should” have ended, before she told me how wrong I was.) But I was like my first friend and had no idea at all what was going to happen next until I typed it, and … it still worked. The story came out. It made a complete arc.

Okay but that’s a success story.

I get it – there are plenty of ways to outline a story or not, and they all work for different people, and look at how well they worked for me! Whee! But what about when something doesn’t work? What about all the failures and the discards and …?

Next post, I promise. We’ll talk about about the failures next. I’m going to need a lot of space for those.