This question’s been going around Twitter lately, so here are my thoughts:

- Yes, because if you have a blog, you have more space to answer questions like this and can link people back to it instead of trying to type out the same answer, but shorter. (I’ve been doing this lately when people ask about academic book proposals: two blog links in one tweet. I’m not crowding your feed, but bam, these are my thoughts.)

- Yes, because it’s a way for people to reach out and contact you. If you’ve ever tried to track down a scholar based on a thesis or dissertation, you might know: .edu emails disappear. They aren’t always checked. Even though my website hasn’t even been around a year yet, I’ve had multiple people contact me through it, either because they’d already read something about me or they googled something about my research and came across it that way.

- Yes, because if you don’t have a website, you’re never going to randomly wake up one morning to a notification that Smithsonian Magazine has linked to it. Okay, that’s very specific, but: if you don’t put things out there for people to find (for free), then these things won’t happen. It’s also a place where you can share your research on a more accessible level, both as in “not behind a paywall” and “I don’t have to put on my ‘scholar voice’ when I write this stuff.”

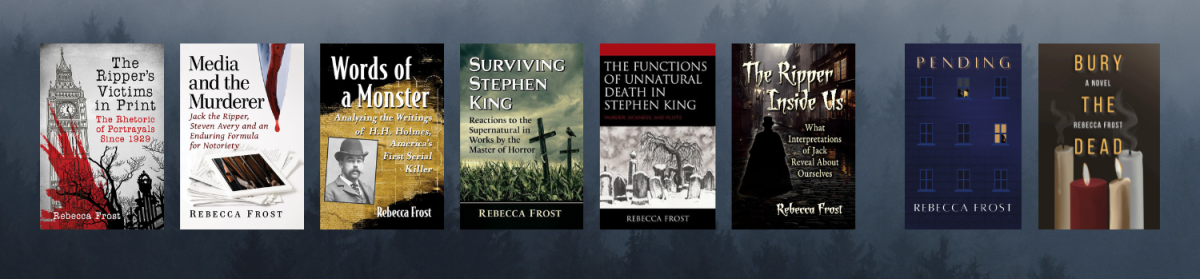

People who are curious about the work I do are more likely to click on a link than they are to buy a book. Especially a book from an academic press – we all know the price tag on those can be higher than average. But, if you read what I post and like what I do, the chances of a purchase go up.

On the other hand, the possible drawbacks:

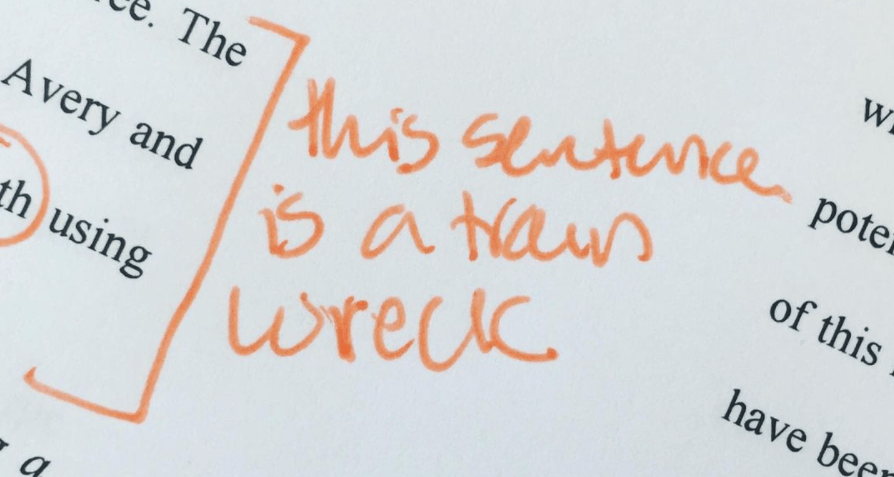

- Starting a blog means having to continually produce content. I draw either from research I’ve already done and published or my interactions with other writers, but it still takes time to write up these posts so that there’s continually something new. Having a static website is still totally recommended because of my second point – giving people a current means to contact you – but, if you’re thinking of going the blog route, it’s another to-do in your list.

- Costs. Depending on the kind of website you want, you might have to budget for it. There are plenty of opportunities for people who don’t know either coding or design (hello!) to set up their own websites, but taking the time to look around and decide which one seems best for you is a cost of its own.

- Overnight success takes a decade. Well, maybe not quite that long, but I looked at this website and blog as a long-term investment. Sure, the views and comments would be low at first, but … maybe … some day … even more things will happen that I never dreamed of. Through all of the “shouting into the void” weeks, though, you still need to be producing content. That’s just something to be prepared for.

What do you think? Do you have your own website? What’s your experience been like?