I did this last week on Twitter, and wanted to compile them and share them here. I got 17 likes, so here are 17 random facts about me as writer.

1. I wrote my first novel-length original fic at age 15 because I couldn’t get my plot to work as a fan fiction.

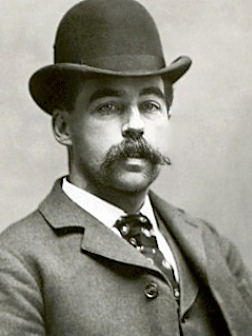

2. My favorite of my published books so far is Ripper’s Victims, because that’s the work closest to my heart. (My mom’s favorite is the one about H.H. Holmes.)

3. I keep track of how much I write each day, but not always in the same place. Sometimes it’s on the NaNoWriMo website, sometimes a sheet of graph paper, and sometimes in my daily planner. (I’ve written over 300k so far this year.)

4. My writing schedule varies wildly. Some days I write 0 words. Others I’m up and at the computer immediately and forget to take breaks for real-life things. It all balances out.

5. In 2020 I decided to complete NaNoWriMo (50k words) in two days, simply because I did it in three days in 2019. I hit 50k by 8pm November 2. And had to baby my wrist for months afterward because … people aren’t meant to type 50k in two days.

6. Because of 5, I taught myself how to dictate my writing, both academic and fiction. I didn’t think it was possible for me but really it’s just the learning curve I didn’t want to tackle.

7. I started lighting a candle when I write as a signal to my brain that it’s time for words, and somehow it’s grown up into this entire thing.

8. The proposal for an academic book is the hardest part for me. I love having swirling ideas and hate forcing myself to commit to a very specific outline. I’ll put off writing the outline as long as possible, even when I know what I want to propose next.

9. I got the contract for Ripper’s Victims because my editor saw my published dissertation and emailed to ask if I had anything she might be able to help me with. (Put yourself out there!)

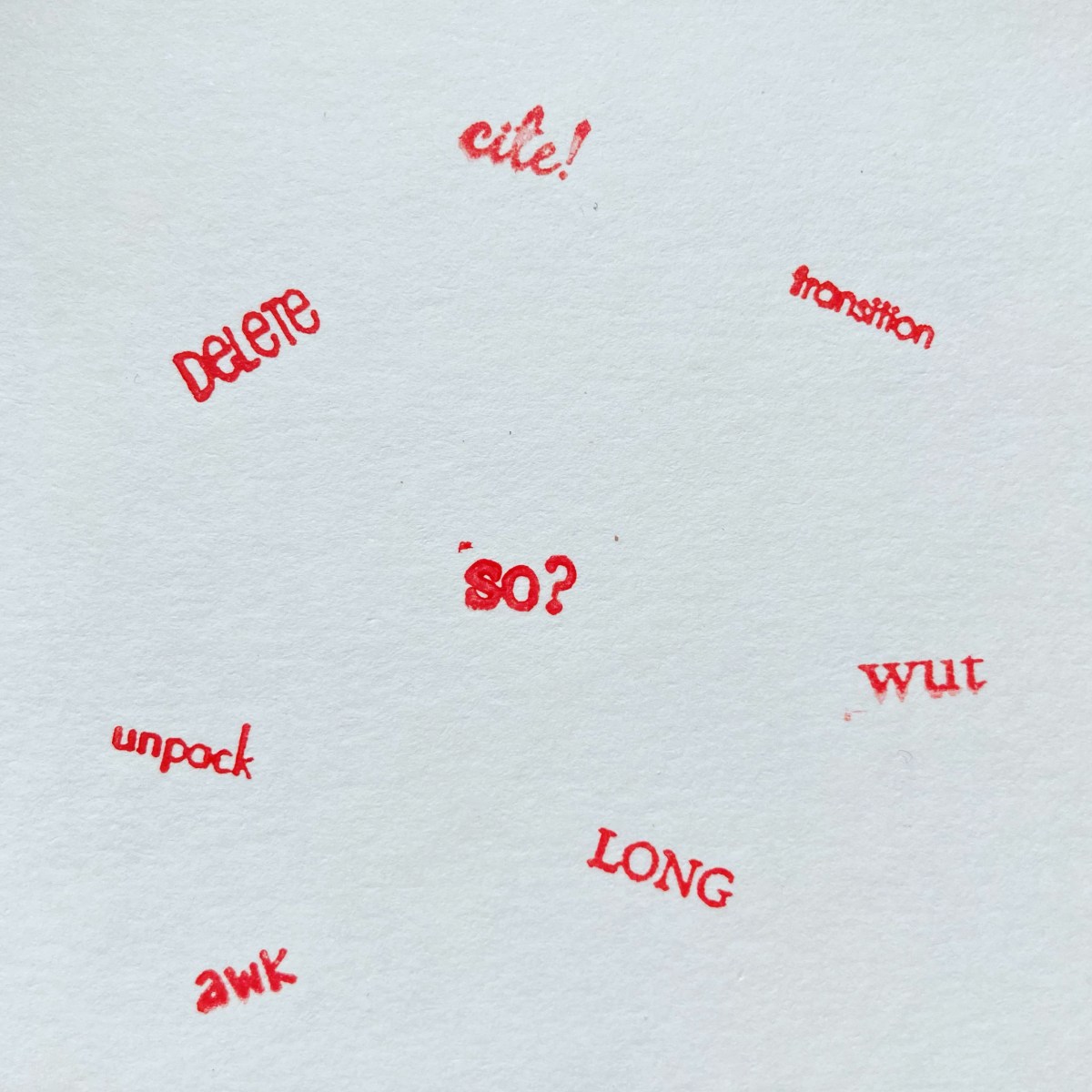

10. When it’s time to edit, I prefer a hard copy to a screen. Considering the usual length of my manuscripts, this generally means going somewhere to have it printed, since our elderly printer isn’t up to the task.

11. Printing things off means I can use my custom stamps. I get tired of writing the same thing over and over on my first drafts so … I had these made. And of course they’re red.

12. When I’m writing fiction, I tend to “cast” actors as my characters. It especially helps when a character is very much not like me – say, when I have someone whose speech patterns are very calm in moments of stress. If I can picture the actor saying it, it helps.

13. I frequently right click to find synonyms for words I’ve used in my own writing that I’m pretty sure mean what they think they mean, just to be positive. Sometimes I realize I’ve used a word that doesn’t mean what I think it means …

14. I used to write all my “novels” by hand, in pencil, and super teeny – two lines of writing per ruled line on college-ruled paper. I did NaNoWriMo by hand in 2013, but otherwise I type the first draft these days.

15. I used to say all my dialogue out loud as I typed it. My brother laughed because he could hear me arguing with myself. I can write out in public now because I don’t have to do that anymore … but some days I still find myself muttering things as I type them, dialogue or not.

16. I don’t like doing book titles, chapter titles, or heading titles. They’re usually last-minute things I put in before I have to deliver something. It’s rare for me to have a title early on in a project.

17. When the words are flowing and the writing is good, I write fast. Really fast. Which makes the slow days feel agonizingly slow.

Share a random fact about yourself below!