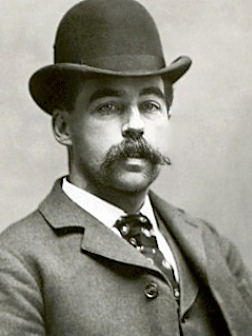

Every serial killer has to start somewhere. The “serial” part means they had to keep going, eventually, but there’s always a first. For H. H. Holmes – at least in his newspaper confession – his first victim was a former medical school classmate, Dr. Robert Leacock.

Holmes attended the University of Michigan for medical school and did indeed graduate. Although “H. H. Holmes” wasn’t his real name, the MD was earned. Many sources trace his murderous intentions back to medical school, where he has also been accused of participating in grave robbing in order to have cadavers on which to learn. This also led to questions of whether enterprising medical students – or those looking to make money off a sale to a medical school – might murder in order to provide the students with learning material.

In his newspaper confession, Holmes actually says very little about Dr. Robert Leacock. He dismisses the murder because it “has been so often printed heretofore” and quickly moves on to the lament that, “like the man-eating tiger of the tropical jungle, whose appetite for bloodlust has once been aroused, I roamed about the world seeking whom I could destroy.” That’s all very dramatic, but it doesn’t tell us much about Leacock.

Earlier, in Holmes’ Own Story, Holmes had written of a previous insurance scam he had run in order to somehow prove that he could not, in fact, have murdered Benjamin Pitezel in a similar scam. The few details he gives about Dr. Robert Leacock’s murder do not quite line up with the information provided in Holmes’ Own Story but, since each is most likely a lie, that’s understandable.

But what’s the tale of the insurance scam he supposedly committed with his former schoolmate?

More than a decade before Pitezel’s death, Holmes supposedly decided to fake his own death using a lookalike cadaver in order to reap the insurance money. (He says that his wife would have been the one to inherit, but his third wife – the one he claimed at the time of the trial – hadn’t even met him yet. Apparently no one caught this inconsistency before his book went to press.) In this version, however, Holmes simply waited for someone to die who would look enough like him to count. He didn’t, according to the book, kill anyone for this scheme.

He also didn’t prepare very well. Holmes wanted to take the lookalike body north into Michigan and leave him, head crushed and with Holmes’ papers in his pockets, to be found and identified. Although Holmes should have had plenty of experience with both cadavers and decay during medical school, he planned poorly for transporting a body secretly by train.

It turns into a whole comedy of errors. The first trunk Holmes had specially made began leaking ice and odors, forcing him to stop and buy a new trunk. It couldn’t be seen to be empty, though, so while the shopkeeper prepared the trunk, Holmes walked back and forth with lengths of pipe he had also newly purchased in order to fill it. Then, when the new trunk was delivered to his hotel, he could pretend that it was full of his belongings.

It didn’t seem to occur to him that anyone involved in this various transactions might notice the oddity and remember him.

While apparently lost in a reverie, contemplating the lookalike corpse who was reclined on more ice in the room’s tub, Holmes’ room was invaded by detectives or secret service men or someone just that exciting. Using lies – common for Holmes – and threats (less common) he managed to get himself out of the initial situation, claiming the dead man was his brother. When Holmes left the hotel, though, he knew he was being pursued. (He was, of course, both interesting and cunning enough that any secret service agent would want to follow.)

Unfortunately for Holmes, the train he took ended up having an accident, delaying him just long enough for the secret service agent to catch up. Holmes did not flee the scene, leaving his suspicious luggage behind. No – instead he put his medical degree to use and cared for fellow passengers who were injured in the crash.

Perhaps since the secret service agent was alone this time, Holmes was able to bribe him, and therefore continue his way north with his smelly, sodden trunk. Holmes sums up the tale quickly by explaining that, a few weeks later, his plan went off exactly as he wished, and he walked away with the insurance money. (His wife, whose presence was never fully explained, is forgotten.)

Later he apparently gifted the trunk to friends who laughed with delight when he told them the tale, because they had always thought it was haunted.

Right. So.

Clearly there are a lot of problems with this story. For one thing, according to Holmes’ Own Story, it should have taken place in the early 1880s. Although he would have indeed been married to Clara (Lovering) Mudgett at that time, during the summer of 1895, when Holmes’ Own Story was published, Holmes was insisting that he was married to Georgiana Yoke and that he had never married another. This was because Georgiana was a witness in his murder trial and, if it were proven that the marriage were bigamous, she could indeed testify against him. Holmes married three women in his lifetime without ever divorcing any of them, and all three were still alive at the time of his death.

There is also the question of the insurance money. Different amounts are stated in Holmes’ Own Story and in his confession to the murder of Leacock. If, for example, Holmes had managed to get his hands on the $40,000 he said came with Leacock’s death, what happened to it? Where was it spent? Holmes never clarifies, and he never explains how he ended up with the money from his own apparent accidental death.

The story as originally told is meant to explain that Holmes, although a rogue, is not a murderer. He waited for a body that would look enough like him to be brought to the morgue rather than searching out his own double and then, even once he started to put his plan into practice, he made a mess of things. Far from being a slick and confident criminal, the Holmes in the original story made mistakes at every turn. He only managed to pull of the scam by bribing someone to look the other way.

It did make for a good story, though, so it also makes sense that Holmes’ confession would reference it. He dismisses a number of people in the same way, but arguing that much has already been written about them, without ever actually clarifying what happened, or how much of what has already been written is true.

Did Holmes actually murder a man named Dr. Robert Leacock in order to fake his own death and reap the insurance benefits? No. This is one of his false confessions, albeit one that may have helped boost sales of his book if by chance some curious reader had missed the adventurous corpse, trunk, and secret service man story.

The order of events is fuzzy and might go a long way to answering whether Julia’s death was intentional. In his newspaper confession, Holmes says that Pearl’s death was due to poisoning, and that Pearl died after her mother. In Holmes’ confession Julia is his third victim, and Peal his fourth – although apparently there was an accomplice in this case.

The order of events is fuzzy and might go a long way to answering whether Julia’s death was intentional. In his newspaper confession, Holmes says that Pearl’s death was due to poisoning, and that Pearl died after her mother. In Holmes’ confession Julia is his third victim, and Peal his fourth – although apparently there was an accomplice in this case.