It’s been a while since I’ve shared some of my research instead of my writing musings, so let’s jump back in to Jack the Ripper and consider a pair of suspects: Joseph Barnett or George Hutchinson. These are an “or” pair instead of an “and” pair, because nobody’s (yet) suggested that they worked together, but the story behind them is very similar.

Both Barnett and Hutchinson are connected to Mary Jane Kelly, the last of the so-called Canonical Five victims of Jack the Ripper. Choosing either Barnett or Hutchinson as the Ripper clearly makes Mary Jane Kelly the last. It actually positions her at the center of all of the murders.

Joseph Barnett was Mary Jane Kelly’s boyfriend. The two of them met in April 1887 and decided to move in together on their second encounter. The vast majority of what we know – or think we know – about Mary Jane Kelly comes from Barnett’s testimony at the inquest after her murder. He lived with her until the end of October 1888, when they quarreled and separated.

Barnett had been living with Mary Jane Kelly at 13 Miller’s Court when they separated. It was a very small room, with only a single bed, and one of the reasons for the separation seems to be that Mary Jane was letting other women sleep there. Since this was the Autumn of Terror where women were being murdered in the streets, and since Mary Jane had a steady room that wasn’t in a lodging house, it seems like it was a kind thing for her to do.

Another instigating factor for their separation also seems to have been the fact that Barnett had lost his job as a fish porter, resulting in Mary Jane Kelly’s return to sex work. Barnett apparently disproved of this as much as he did of her offering their small, shared space to other women, and so he left her. Their separation was the reason why Barnett was not also sleeping at 13 Miller’s Court the night of November 8-9, and why Mary Jane Kelly was alone and murdered there.

Barnett was not a suspect at the time. In fact, Inspector Fredrick Abberline personally cleared him after a four-hour interrogation, which included an inspection of Barnett’s clothes. No blood was found, and Abberline, at least, was satisfied.

The same cannot be said for Bruce Paley who, in 1996, named Barnett as the Ripper. According to Paley, Barnett decided to become the Ripper in order to scare Mary Kelly off the streets and force her to stop making money through sex work out of fear of being murdered. On the one hand, Barnett’s plan seems to have worked if Mary Jane Kelly was worried enough to allow other women to sleep indoors with her. On the other, he apparently couldn’t scare her enough to stop. Thus, Paley argues, Barnett was driven to kill the woman he loved because he couldn’t save her otherwise.

George Hutchinson also became a Ripper suspect not in the 1880s but in the 1990s, this time in a 1998 book by Robert Hinton. Hutchinson was known to the police at the time because, after Mary Jane Kelly’s murder, he made a statement to the police about a man he had seen with Mary Jane Kelly shortly before her murder. Hutchinson, unemployed, apparently had plenty of time that night to hang around Miller’s Court and get a good look at anyone who passed by.

Abberline also interviewed Hutchinson, although he was considered only as a witness and not a suspect. Hutchinson had known Mary Jane Kelly for three years and his incredibly detailed description of the man entering the room with her was explained because Hutchinson thought the man looked “foreign,” which piqued his interest and concern. After all, women were being murdered, so of course he would memorize every detail about any man who seemed to be going into his friend’s room as a client.

Although numerous skeptics have doubted Hutchinson’s description of the Ripper, he wasn’t accused of being the murderer himself until Hinton. And here the story sounds very similar: angry that Mary Jane Kelly was supporting herself through sex work – and not relying on him as her sole sexual partner and source of money – Hutchinson orchestrated the Ripper murders, hoping to scare Mary Jane Kelly into stopping.

Hinton suggests that Hutchinson, after seeing Mary Jane Kelly take that client into her room and that client later depart, snapped. Hutchinson therefore went into 13 Miller’s Court himself, shook Mary Jane Kelly awake – or tried to, considering the reports that she was very drunk that night – and was confronted with the reality of the woman she was instead of the apparent perfection he had preciously imagined. With this ideal shattered, Hutchinson lashed out and killed her.

So: two men who knew Mary Jane Kelly, and were known to have been close to her at the time of her death. One of them was cleared as a suspect by Fredrick Abberline, and the other never even considered to be one. More than a century after the Ripper murders, each in turn became accused of being the Ripper to turn Mary Jane Kelly away from sex work … and into his arms.

What do you think? Was there something in the air in the 1990s? Would a man ever actually turn to serial murder as a way of pursuing the “perfect” woman? Or should we let Barnett and Hutchinson rest in peace?

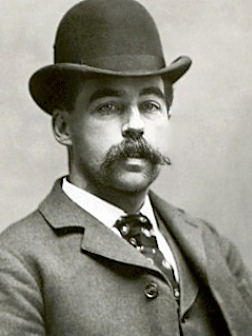

The order of events is fuzzy and might go a long way to answering whether Julia’s death was intentional. In his newspaper confession, Holmes says that Pearl’s death was due to poisoning, and that Pearl died after her mother. In Holmes’ confession Julia is his third victim, and Peal his fourth – although apparently there was an accomplice in this case.

The order of events is fuzzy and might go a long way to answering whether Julia’s death was intentional. In his newspaper confession, Holmes says that Pearl’s death was due to poisoning, and that Pearl died after her mother. In Holmes’ confession Julia is his third victim, and Peal his fourth – although apparently there was an accomplice in this case.